No Big Wahoo

Wait…why is there a Native American warrior on my elementary school writing tablet?

Working so intimately with outdated print materials often makes me wonder what brought them into existence in the first place.

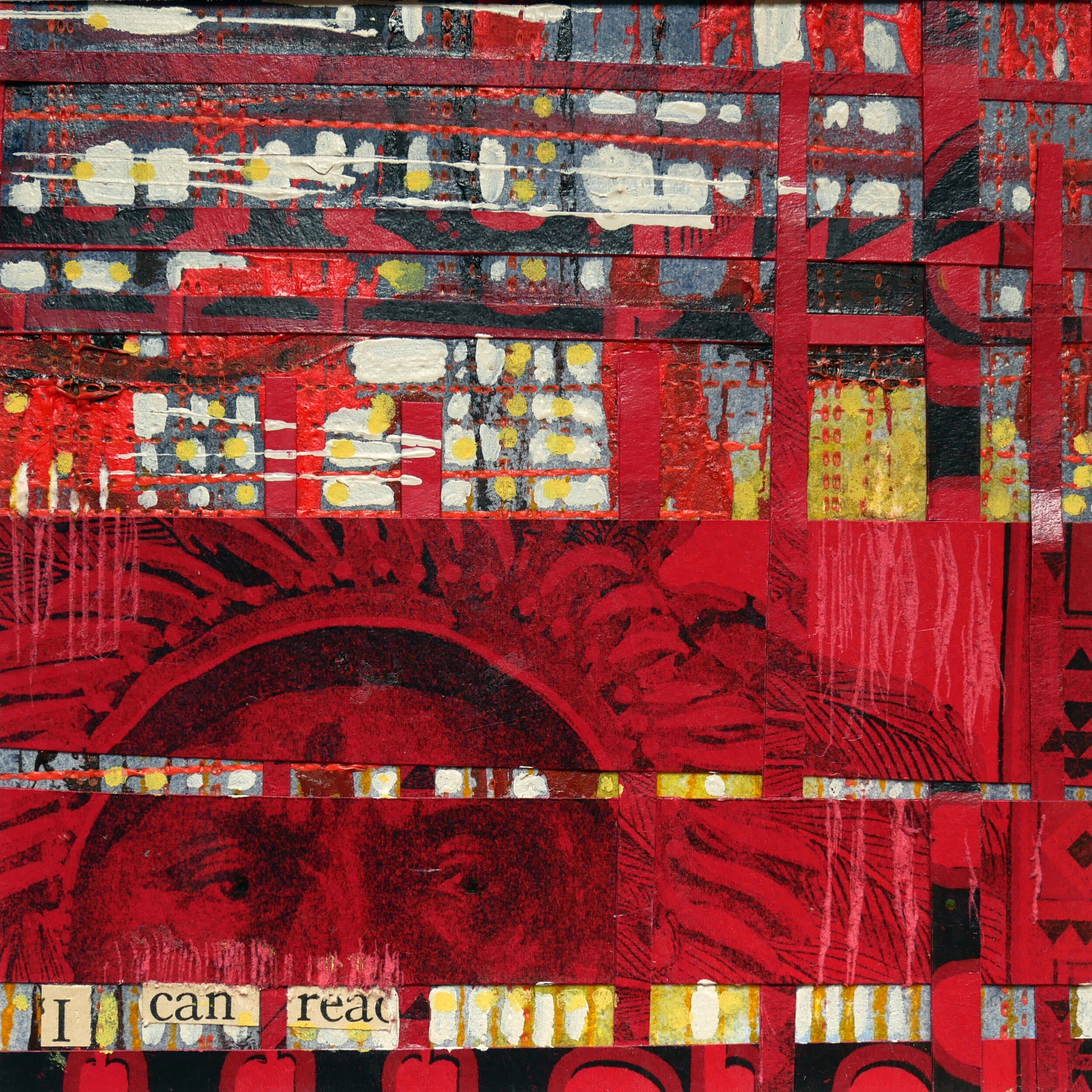

During this past year, various sports organizations and consumer products came under scrutiny for the use of race-based mascots and logos, including the Cleveland Indians, the Washington Football Team (formerly Redskins), Uncle Ben’s Rice, Aunt Jemima Syrup, and the Land O’Lakes Indian maiden logo. Around the same time, I was working on some small paper collages using vintage reading primers and those Big Chief writing tablets…you know, the red ones with the large Indian head on front? I used to love those tablets.

Wait…why is there a Native American warrior in full headdress on the cover of an elementary school writing tablet? Using vintage materials —like the Big Chief writing tablet— in my artwork forces me to question why some images have become embedded in our cultural narrative. I wanted to know the Back Story of Big Chief.

The Big Chief tablet was for many years the most popular brand of paper writing tablet among school children and hopeful novelists in the United States, including fictional characters like John Boy Walton. Some have argued that the texture of the newsprint creates the smoothest transfer of pencil lead. The Big Chief tablets were favored by elementary teachers because the lines were wider apart than regular lined paper which made more room for learning to print letters and cursive writing.

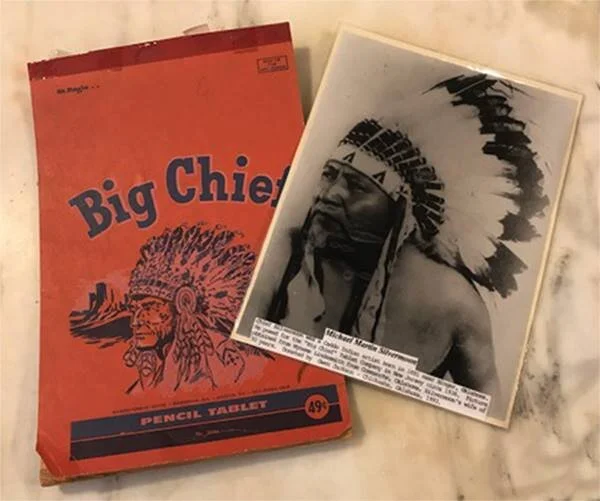

The Western Tablet Company of St. Joseph, Missouri trademarked the Big Chief logo for tablets in 1947 but sold the company and logo to the Mead Corporation in 1966. The tablet lost market share to the formidable spiral notebook and ultimately ceased production in 2001. Eleven years later, American Trademark Publishing of Brookshire, Texas resumed production of the Big Chief writing tablets, incorporating reproductions of nine of the original Big Chief Tablet illustrated covers, which ranged from the stoic to the psychedelic.

But who was the original Big Chief?

Research suggests that Big Chief is modeled after Michael James Martin aka Silver Moon, a Caddo Tribe member born in Binger, Oklahoma in 1891. Early in his career, Silver Moon worked in the library of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, translating the Caddo language for a Caddo Indian-English dictionary. During that time, he posed for Hubard Zettling, sculptor at the museum, and it is this image that Western Tablet Company allegedly used on the original Big Chief tablet logo.

Chief Silver Moon, the Artist

In addition to several appearances on the silver screen alongside the likes of John Wayne, Silver Moon himself was an artist, with his works on display at the Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City and Midwestern University Museum in Wichita Falls, Texas. Silver Moon painted landscapes and portraits of Native Americans on unusual bases such as buckskin, rough wood, velvet, and murals on various textures of cloth.

I’m not sure any of this gets us closer to answering our original question: why is there a Native American warrior on grade-school writing tablets?

Finding no scholarly opinions, I am going to look to A Christmas Story, or more accurately Jean Shepherd's 1966 book In God We Trust: All Others Pay Cash, on which the movie was based, specifically the scene where Ralphie uses his Big Chief notebook to decode the secret message from the Little Orphan Annie radio show. Ralphie, like many other little boys of the 1940s, coveted a Red Ryder Carbine Action 200-shot Range Model air rifle to play the part of a Western hero. And who did Western heroes encounter almost daily? Indian chiefs, of course! Excitement! Adventure! Courage!

So, if you happened to manufacture something rather mundane, say writing paper, whose primary target was little boys (little girls had their sewing and cooking and whatnot)…and little boys didn’t care much about school (see Ralphie)…but little boys did love excitement-adventure-courage (again, Ralphie)…and they loved playing Cowboys and Indians (yes, yes, Ralphie)…well, I think you see where my hypothesis is going.

Only problem, those same little boys liked playing Good Guy vs Bad Guy (see Ralphie’s Black Bart bandit daydream), so the implication is that in the Cowboy/Indian variation, the Indian is the bad guy. The stereotype of “redskins” carrying “tomahawks and knives,” permeated the times. We hang onto these trademark visuals because those of us who are not represented by these stereotypes associate the product with fond memories. But assuming someone who identifies with that group takes offense at this trademark representation—which Native American organizations certainly do—regardless of the consumers’ intent in buying the product, why should we be entitled to hang onto that imagery simply to indulge our sentimentality?

I’m not going to lie. I have fond memories of my Big Chief tablets. But I don’t think Chief made me a better writer, and I probably didn’t make Native American culture stronger by purchasing the tablets with his likeness, unless Chief was getting some royalties, but I’m pretty sure that wasn’t the arrangement.

Besides, little kids don’t even learn how to write cursive anymore. But that’s for another post.